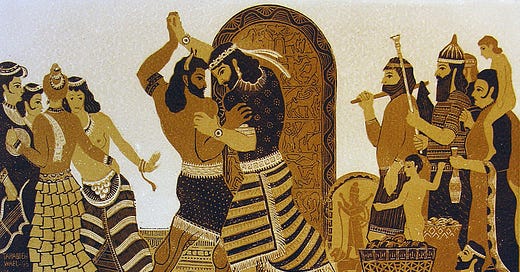

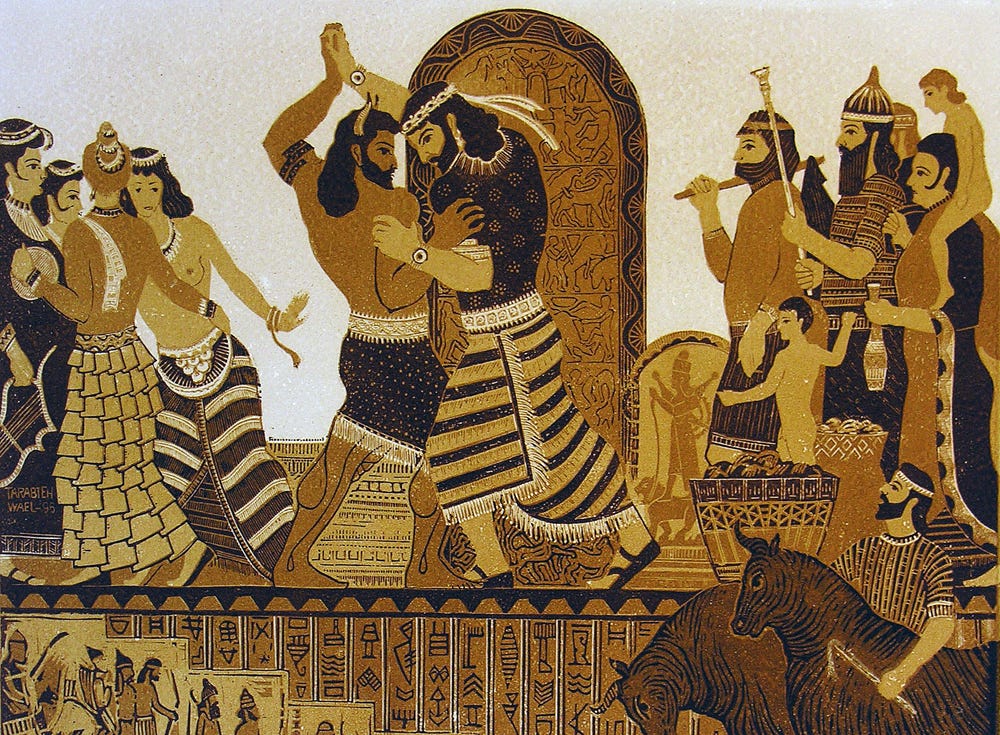

Were Gilgamesh and Enkidu, the two protagonists of the Ancient Mesopotamian “Epic of Gilgamesh,” gay?

Different people give different answers to this question. Some call their relationship a kind of “proto-homosexuality”, others say that there are “allusions” in the Epic that could imply the characters are gay. Scholars, mostly historians, have argued for and against various interpretations of sexuality in the Epic for decades. This Hot Queer Debate™ is expected with any ancient literary work. For another example, see the queer scholarship surrounding the Bible.

But me, personally? Well, I think it’s pretty obvious Gilgamesh and Enkidu are gay.

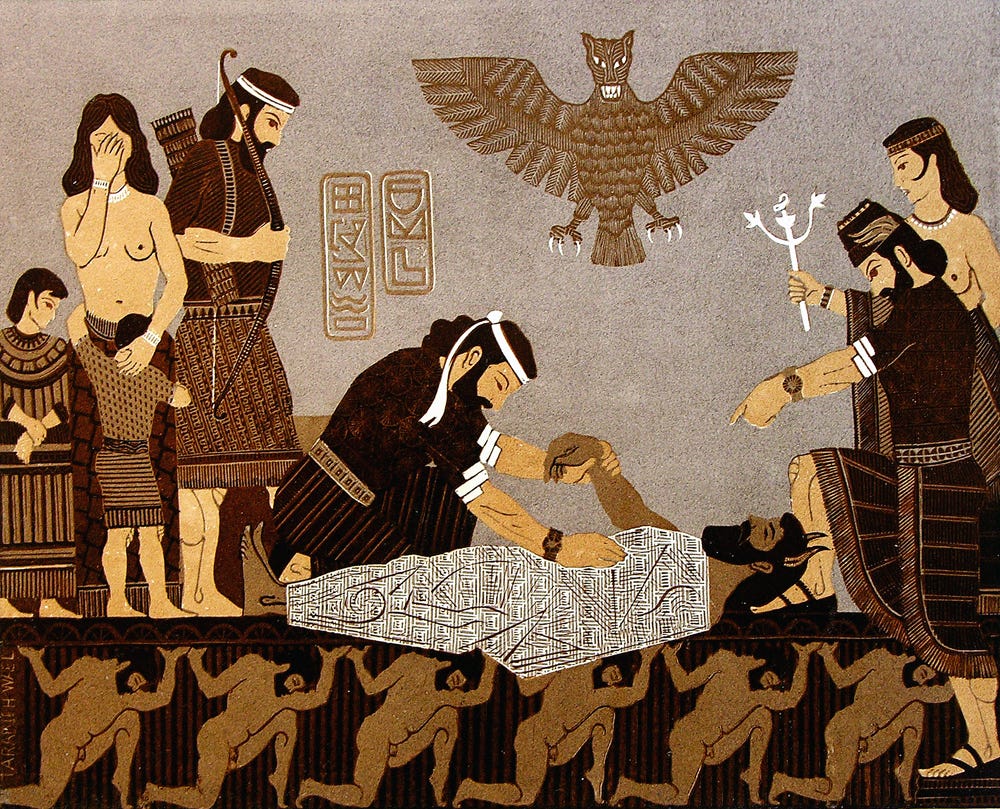

To back up this opinion, though, there are actually some pretty good examples of Gilgamesh’s “non-heterosexuality” in the text of the Epic. The most striking one is in Gilgamesh’s first dream of Enkidu. When Gilgamesh and his mother talk about his foreboding dream of an axe, she tells him:

“The axe which you saw [in the dream] is a man,

You will love him and embrace him like a wife.”

I mean—come on. There’s no heterosexual explanation for that, right? Gilgamesh dreamed of an axe, which his own mother saw as a man, whom he would love and embrace “like a wife”. It’s no mystery what she’s talking about.

And speaking of innuendos, let’s look at another episode from early in the Epic. When Gilgamesh has taken over the city of Uruk, his oppression and tyranny are so terrible that Enkidu is created by the gods just to stop him. And as it happens, one of the tyrannical things Gilgamesh does as the ruler of Uruk is this:

“[Gilgamesh] was mounted on the hips of a group of widow’s sons.”

Now, allegedly this is just a game Gilgamesh is playing with the widows’ sons. It just so happens to be one where he “mounts” their “hips” and “rides” them… Now come on. Even translated into English, there are some obvious sexual undertones there.

And that’s not just me saying so! In fact, one scholar, when exploring the queer interpretations of the Epic actually remarks that in the Akkadian language, the verb “mount” used in this sentence was commonly used to refer to “animal copulation.” That’s some more pretty convincing evidence that this is a sexual innuendo.

Still, these scholars claim, innuendo and implication are not enough to claim anything about the sexuality of either hero of the Epic. They aren’t wrong, of course. It’s flimsy evidence. But I think they’re a little too quick to minimize the role of homosexuality in understanding Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship.

It isn’t useful, they say, or even meaningful to argue for homosexuality existing in the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Ancient Sumerians had no terms for “gay” or “straight” individuals. The work isn’t even about homosexuality, it’s a piece of epic literature. Terms of like “gay” or “homosexual” are totally anachronistic to Ancient Mesopotamia.

So, on one hand, we have some readers (myself included) who say the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is homosexual. And on the other hand, we have some historians claiming this label is meaningless to use in the ancient world.

With all due respect, I will try to disagree with them in this article. I want to argue that, while it may not be correct to call ancient relationships “homosexual” in a strictly historical sense, we risk missing out on an emotional, artistic connection to the work if we historicize the Epic of Gilgamesh this way.

To disprove the existence of homosexuality (as we know it today) in ancient Mesopotamian literature, historians tend to cite ancient Assyrian laws that were in place around the same time as the Epic was first conceived.

These laws persecute the “penetrated” male in a homoerotic sexual act, and so it’s argued that ancient people saw homoeroticism through the lens of domination and power. The same domination and power, notably, that were already codified by this time in heterosexual relationships. In other words, it wasn’t so much your gender that mattered, but whether you were submissive or dominant during sex.

Historians further argue that homoeroticism, therefore, was not seen as a legitimate form of romantic or sexual expression, but as a tool of domination in a patriarchal society. “[T]he ancient world was heteronormative”.

Homoeroticism in the ancient world was just an extension of regular old patriarchal, oppressive, and violent heteronormativity.

But can we deconstruct this heteronormative homosexuality?

Well… let’s try to, with queer theory.

Is it possible to “queer” the Epic of Gilgamesh? What does it mean to “queer” something in the first place? Well, I like working with Wendy Gay Pearson’s definition:

“Queer suggests a move not just towards a different conception of sexuality, but also towards a different understanding of subjectivity and agency.”

So, in other words, to queer the Epic of Gilgamesh, we’re going to need to look at how sexuality manifests in the text. We’ll also need to inspect our subjective views of the Epic, and our agency in the act of “queering” itself.

Firstly—sexuality. One interesting thing to note here is that, in the actual text, the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is only ever platonic and heterosexual. Anything more can only be supposed though subtext.

There is no actual “homosexual behavior” in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

And if you’ve noticed, all the “evidence” I gave earlier, and all we’ve talked about up to this point, has been purely subtextual. It’s all been hidden meanings and different people’s interpretations, trying to figure out if Gilgamesh and Enkidu are gay.

Interestingly enough, queer theory is, at its core, very interested in individuals’ opinions, and how, why, or why not people express those opinions. Someone’s interpretation of a text, whether it is the author, reader, or a historian, is an entirely unique subjectivity. And their agency is the willpower (or lack thereof) that they have to put that view out there into the world. Like I’m doing now, for example.

So, if modern readers can broadly interpret the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu either as gay, or queer, or homoerotic, or even “an example of romantic love between two men,” then these interpretations are all important in the process of queering Gilgamesh.

Queer literature in history cannot be monolithic, precisely because it’s so human. Reading into an innuendo or interpreting dreams is, much like reading into a suggestive look, or interpreting a flirtatious gesture, emotionally driven and entirely subjective. Queerness takes pleasure “in resisting attempts to make sexuality signify in monolithic ways” (Pearson again).

We can’t say for certain whether Gilgamesh or Enkidu were or were not “homosexual” because all sexuality is inherently subjective and very personal.

There is no historical, textual, or theoretical evidence that will ever be enough to prove the exact nature of their relationship. Our own, subjective interpretation will have to do.

While most scholars I’ve read and talked about today have nuanced views about the Epic and its portrayal of homosexuality (or apparent lack of it), I think that their views are still limited. In trying to historicize the Epic of Gilgamesh, in treating it purely as an artifact of ancient Mesopotamian culture, we minimize the importance of it as a work of literature, and our connection to it as a work of art.

Neither the Epic itself, nor the texts of some ancient Assyrian Laws that potentially disprove that Gilgamesh and Enkidu could’ve been secretly making out between scenes, nor any piece of history can hold some innate “truth” about homosexuality in the ancient world. The “truth” of history is totally subjective, and ideological.

John Berger’s landmark work “Ways of Seeing” is (yet again!) helpful in making sense of this subjectivity of history.

Berger says that the past is never static, “never there waiting to be discovered.”

Instead, history consists of the present, and its relationship to the past. Trying to look to the past for “truth”, citing ancient Assyrian laws to “prove” that Gilgamesh and Enkidu couldn’t have been romantically or sexually involved with each other is only another kind of subjectivity.

Understanding that we observe the past through the lens of the present, we are able to begin the process of queering history itself.

None of this is to dismiss the work of all these historians. Of course, the historical research and archeological work done to be able to make claims about obscure Assyrian laws from millennia ago is important. It’s only that, in attempting to answer questions like “are there homosexuals in Ancient Mesopotamian literature”, historians tend to favor finding “truth” or “objectivity” where no such thing is possible.

I want to wrap this up with a little thought-experiment. Let’s imagine the world in which The Epic of Gilgamesh was composed. Much like today, there were definitely people in those times who were attracted to the same sex as themselves. Those people didn’t call themselves homosexuals, maybe, but they had similar experiences, desires, and suffered under a similar patriarchal system as LGBTQ+ people today. And just like today, homosexual acts were socially stigmatized for them, punishable by law, and by death.

So despite the fact that ancient Mesopotamians did probably see homoeroticism differently to how we see it today, all the way in 2024, we still have something in common with them. We share problems, experiences, oppressive systems. Therefore, we might also share common emotions and interpretations of the world.

Much like our modern world, the ancient world was heteronormative and patriarchal. And while the people in that world didn’t identify themselves as homosexuals, what’s much more important is that we can relate to those ancient people. We can still find our own subjective meaning in the characters of their stories, and identify in very personal ways with their struggles.

While it’s important understand the facts of history, we shouldn’t stray into the realm of what John Berger calls cultural mystification, or “explaining away what might otherwise be evident”.

In striving for exactness in historical discovery and theory, we shouldn’t “explain away” how we respond to the art of the ancient world.

While the ancient Mesopotamians didn’t write their literature with contemporary ideas about sexuality in mind, contemporary ideas about sexuality can still be applied to ancient works of art, because we, contemporary people, are the ones experiencing them.

Therefore it’s possible, and even desirable to queer the Epic of Gilgamesh. And we can (and should) use literary analysis, historical analysis, our emotions and experiences, anything at all really, to make it happen.

This article is a short version of a paper I wrote for my World Literature class in university. If you want to read the whole thing or look through the bibliography, you can find the paper here.

Not gay. He had sex with a woman for 7 days and seven night.... it also says his penis was erect... meaning he is a man and was depicted as such. End this brainless takes....